What is it about mysteries that entice and tantalize us, leading us down shadowy corridors of the human psyche? Welcome to a tale that combines the thrill of uncertainty, the chill of cold-blooded cunning, and the strange fascination of a notorious sadist. This is the story of Sylvestre Matuska, a man whose deadly fascination with trains crossed continents and etched a violent path into criminal history.

In the years following the First World War, Europe was shrouded in political and economic unrest. It was amidst this landscape that a series of catastrophic train explosions began to occur, leaving communities terrified and authorities bewildered. One of the most notorious attacks took place on August 8, 1931, on the Basel-to-Berlin express near Jüterbog. The explosion injured 100 passengers, some of them seriously, and fear spread across the continent. This was not an isolated incident. Earlier that same year, there had been an unsuccessful attempt to derail a train near Anspach, in Lower Austria. Given the political climate of the time, theories quickly began to circulate that these atrocities were committed by the same man – potentially for political motives.

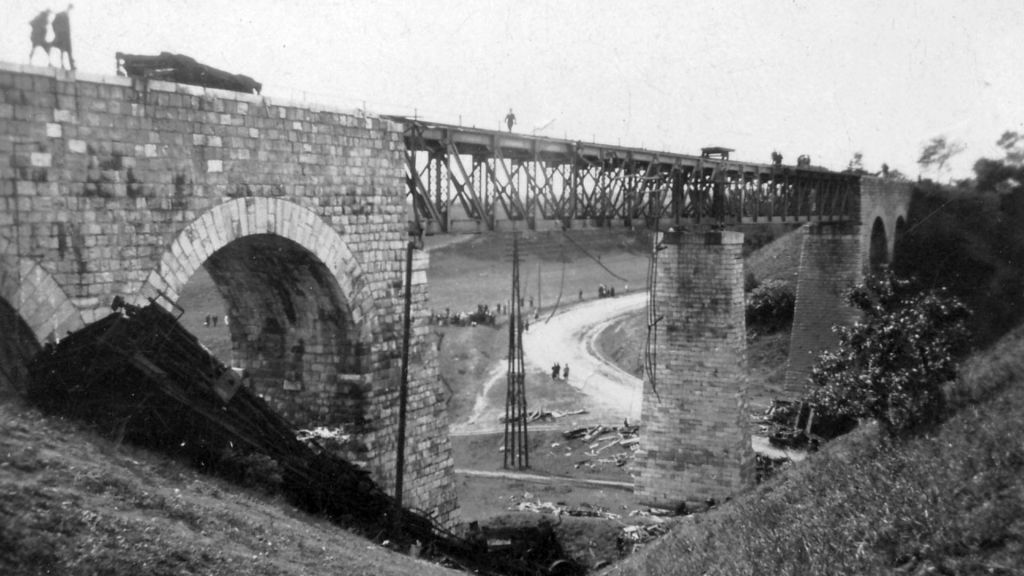

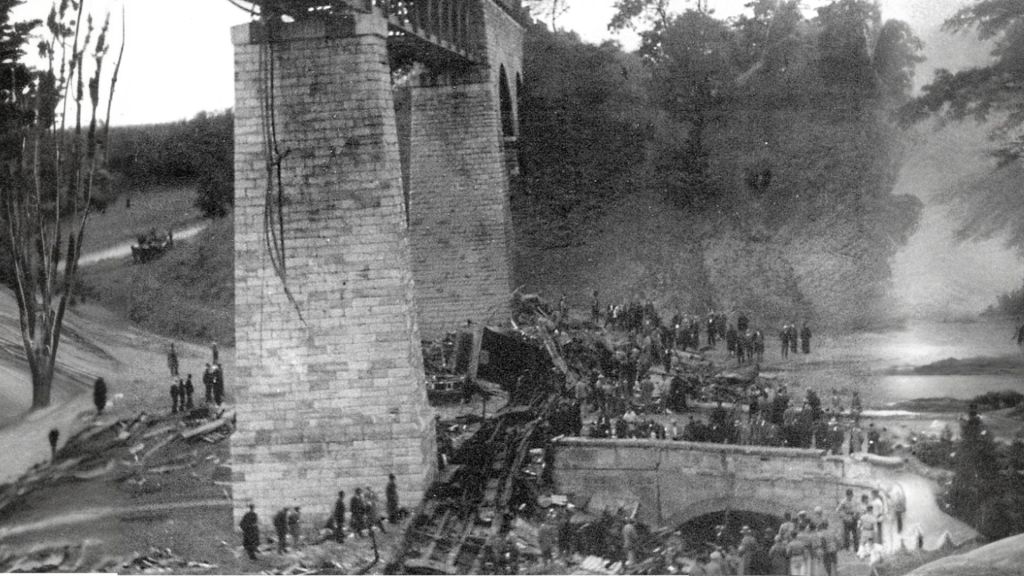

Then, just a month after the Jüterbog attack, another explosion occurred. On September 12, 1931, the Budapest-Vienna express was crossing a viaduct near the station of Torbagy when a tremendous blast shook the train, hurling five coaches into the depths below. Twenty-two people were killed, and many more injured.

The Vienna Morning Post dispatched a 20-year-old reporter named Hans Habe to the scene of the disaster. The grim scene was chaotic: ambulances rushing to and fro, stretchers carrying away the injured, and the morbid sight of wooden coffins beside the track, bearing the victims of the tragedy. Some victims had been blown into pieces, a horrific detail that Habe would later include in his report.

Amid the chaos, Habe encountered a man who introduced himself as Sylvestre Matuska. Matuska, a short, well-built man with a military-style haircut, claimed to be a Hungarian businessman who had miraculously survived the explosion, having been in one of the wrecked carriages that lay below the viaduct. His lively, friendly demeanor, and his apparent escape from death’s door seemed to warrant attention. Habe gave him a lift back to Vienna and later met him in a café where he found Matuska captivating an audience with his account of the disaster, complete with detailed sketches.

However, Superintendent Schweinitzer, in charge of the investigation, was not so easily swayed by Matuska’s charisma. There was something that didn’t sit right with him. Matuska looked too healthy, too unshaken for a man who had supposedly survived a train wreck. And as he began to question the surviving passengers, none could recall seeing Matuska.

The forensic evidence also began to paint a disturbing picture. The train, it appeared, had been blown up by an “infernal machine” in a brown fiber suitcase – effectively a mine triggered by the weight of the train. The level of sophistication and the quantity of explosives used were significant, suggesting the involvement of someone who knew exactly what they were doing.

Thus began the unraveling of the charismatic Hungarian businessman’s tale, a descent into a rabbit hole that would lead to one of the most notorious criminal investigations of the post-war era.

Unmasking the Puppeteer

When the world began to recover from the shock of the tragedies, the investigators focused on Matuska. He was living under the guise of a Hungarian businessman, but the authorities were starting to doubt his innocence.

Days after the Torbagy express explosion, an unexpected lead arrived at the Vienna police in the form of a taxi driver. The driver recalled being hired by a short-haired man for a lengthy journey to two munitions factories, where the man had purchased sticks of dynamite.

This information raised immediate questions: how had this man managed to obtain a permit for explosives? Who was he, and what were his intentions? The answers began to materialize when a woman named Anna Forgo-Hung came forward with a critical piece of information. Sylvestre Matuska had approached her with an interest in leasing her property, specifically, a quarry. He explained his need to perform some blasting, a seemingly innocuous requirement that had allowed him to obtain a permit for the explosives.

The pieces of the puzzle were starting to fit together. The authorities arrested Matuska, charging him with the bombing of the Torbagy express. Upon hearing the news, reporter Hans Habe visited Matuska’s wife, a soft-spoken blonde woman who staunchly defended her husband, declaring his innocence. Yet her insistence seemed somewhat hollow; she discussed tickets and other “proofs” of his innocence, but her demeanor suggested underlying doubts.

The story took another dark turn when Matuska confessed to the charges. He admitted to being on the Budapest train and disembarking at the next station, hiring a car, and driving to Torbagy just in time to witness the explosion he had orchestrated. Forensic examination of his clothes from that day showed semen stains, leading to the involvement of psychiatrists who concluded that Matuska was a sadist. Moreover, he was described as a man with an insatiable sexual appetite, often sleeping with different women while away on his business trips.

The trial began in Vienna on June 15, 1932, with Matuska presenting himself as oddly effeminate in court. From the onset, he appeared to play the card of insanity, weaving a tale of persuasion by a right-wing guru named Bergmann, spiritualist séances, and occult influences dating back to his early teens. In a particularly peculiar display, he referenced the electric train set he had bought for his son, on which he spent more time than the child.

The jury, however, was not swayed by Matuska’s attempts to cloak his heinous crimes in mysticism and occultism. The weight of the evidence was too substantial, and Matuska was sentenced to life imprisonment, the harshest penalty under Austrian law. Subsequently, he was retried in Budapest, where he was sentenced to death. However, due to the life imprisonment sentence from the Viennese court, the death sentence was not executed.

With the gavel’s fall, it seemed the macabre tale of Sylvestre Matuska had reached its conclusion. Little did the world know, it was far from over.

Re-emergence: Matuska, the Phantom of Chaos

When the Second World War concluded, the world began to piece itself together once more. Among the many lost threads of history was that of Sylvestre Matuska. His story resurfaced when a reporter questioned Hungarian authorities about his fate. Following a series of evasions, the authorities disclosed a stunning revelation: Matuska, the infamous train-wrecker, had been released.

This alone would have been an alarming update for the world that knew him as a dangerous criminal, but Matuska’s story had yet another chilling chapter. In 1953, near the end of the Korean War, an American patrol near Hong-Song apprehended a group of North Korean commandos attempting to blow up a bridge. Leading them was a white man, who, after extended interrogation, declared, “I am Sylvestre Matuska.”

The significance of his identity seemed lost on his captors, prompting Matuska to explain further, “I am Matuska, the train-wrecker of Bia-Torbagy. You have made the most valuable capture of the war.”

As it turned out, Matuska had been freed from his Hungarian prison by the Russians, who utilized his skills for their interests. He claimed to have wrecked the Jüterbog train on the orders of a Communist cell to which he belonged. His admission earned him a place among the North Korean forces, where his expertise in sabotage could be put to use.

Reporter Hans Habe speculated that Matuska may have divulged Communist military secrets to the Americans, possibly leading to his release. Yet again, Matuska slipped through the fingers of justice and vanished. The man once known as the ‘train-wrecker,’ the puppeteer of chaos, disappeared without a trace. His fate following the Korean War remains an enigma.

The story of Sylvestre Matuska is a chilling reminder of the depths to which human depravity can sink and the disturbing pleasure one man derived from the chaos and destruction he orchestrated. A narrative woven through the fabric of history, filled with horrific acts of violence, cold calculation, and a dark passion for devastation, his tale continues to haunt the world of true crime, lingering as an eerie specter in the annals of criminal infamy.